Displacement, Devastation in Western Alaska

Remnants of Typhoon Halong ravaged the Y-K Delta with floods, displaced thousands, removed homes from foundations, flooded critical infrastructure, and destroyed indigenous winter food stores.

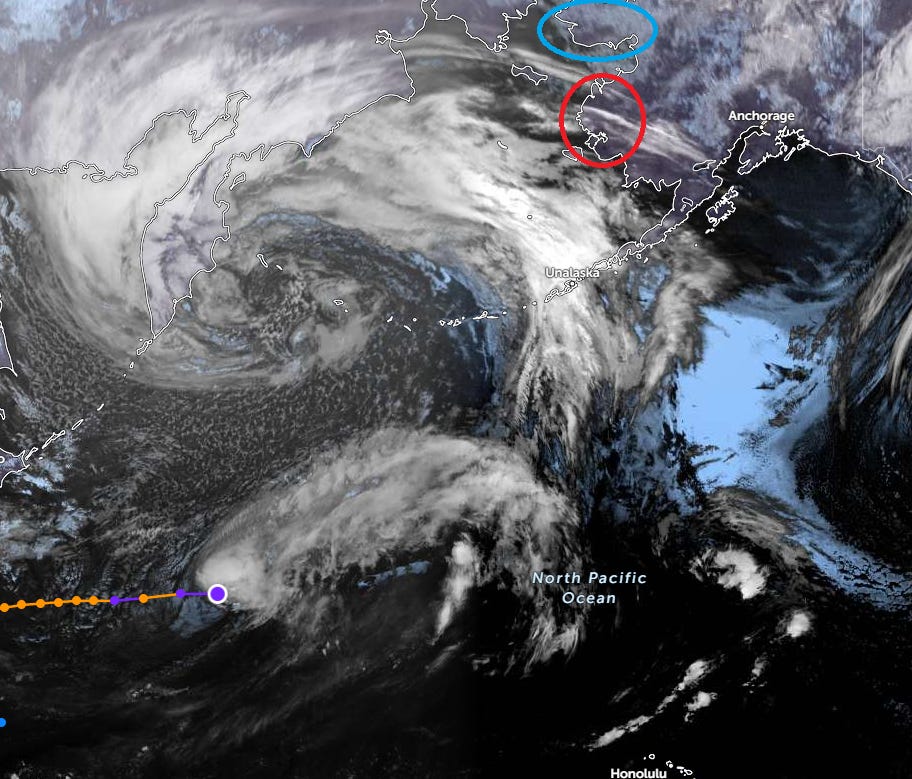

Zoom.Earth. Typhoon Halong 2025. Alexandria Rose. Structures In The Wild. Area in Blue highlights the expected impact zone. Area in Red highlights the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta area most impacted by remnants of Typhoon Halong.

Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska, Sunday, October 12th, 2025 — Typhoon Halong formed as a tropical storm on 5th October, growing quickly into a Category 4 typhoon. On October 7th, it peaked in strength before making landfall on Japan’s Izu Islands as a Cat. 3 storm. Typhoon Halong moved Eastward into the Pacific and weakened into an extratropical system. While not a full-blown typhoon, extratropical systems still produce heavy winds and storm surges consistent with powerful meteorological phenomena. These remnants tracked across the Aleutian Islands and into the Bering Sea.

While the Extratropical Cyclone itself was expected to move northward towards Nome near the Bearing Strait, Halong’s remnants defied expectations. Erik Stone & Evan Erickson of Alaska Public Media reported NOAA issued warnings for “communities from the Kuskokwim River to Wainwright on the North Slope, and high wind warnings that stretch as far north as Kivalina.” However, this would not come to pass. Evan Erickson, Samantha Watson, et. al. of KNBA wrote: “the storm’s track shifted eastward, reducing the winds and water rise originally forecast for St. Lawrence Island, Little Diomede and parts of the Seward Peninsula. Instead, the remnants of Typhoon Halong hit the [Yukon-Kuskokwim] Delta hardest.”

Because of the sudden and unexpected nature of the storm’s turn toward the Y-K Delta, residents were left unprepared and unprotected. The forecast had predicted minimal effects. Local communities were not prepared for this new and sudden reality.

Y-K Delta Impact

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta’s flat topography lies very close to sea level, making it vulnerable to storm surges. The delta has a very small difference in elevation between land and sea. Climate change has led to increased storm intensity and rainfall, overwhelming the delta’s drainage. The changing climate has also thawed permafrost, causing land subsidence — the gradual or sudden sinking of the Earth’s surface due to the subsurface movement of earth materials. Global sea level rise has created an increased risk of flooding by raising the base water level. These combined effects have left the region open to powerful storm surges.

Halong’s extratropical system exploited this vulnerability and flooded villages as far as 60 miles up the Yukon river. Thousands in the region have been displaced. Alaska Army National Guard, Alaska Air National Guard, and the US Coast Guard were activated and sent to the villages of Kipnuk and Kwigillingok on Sunday. Renee Straker of The Weather Channel writes: “One woman died and two people remain unaccounted for, after the remnants of Typhoon Halong brought destructive winds and devastating floods to communities on the coast of western Alaska.”

Alaska Division of Homeland Security Management, Oct. 10, 2025. Flooding in the Y-K Delta from remnants of Typhoon Halong.

Rescue and recovery efforts face major challenges. Unlike the lower 48 states, remote Alaska does not have the shopping district staples, like Home Depot and Lowe’s, for people to rush out to and gather supplies. There are no hotels for the displaced to take refuge in. Limited infrastructure and geographical isolation mean that remote communities have limited access to emergency services, hospitals, and the lack of a robust transit system. When land infrastructure is rendered inoperable due to storm damage, rescue and recovery efforts must first face this bottleneck.

Indigenous communities have been hit hardest with widespread destruction of homes, loss of key infrastructure, the loss of the fall harvest and subsistence foods vital for winter survival, and displacement of thousands of residents. Home heating stoves, sewer systems, and clean-water wells have been lost. Damage has been sustained to roads, boardwalks, boats, and airfields. These lifelines are the main links to greater Alaska.

The indigenous community has already been left to its own devices in dealing with erosion’s impact on infrastructure before the arrival of Typhoon Halong. Paula Dobbyn of Sea Grant Alaska wrote, quoting David Holen in August 2018, that “The village of Napakiak lost about 75 feet of coastline in recent storms, threatening key buildings and infrastructure.” She stressed, “The community had to scramble to move important structures and is now looking at moving its tank farm and school, which are imminently threatened.”

Further cuts to NOAA and FEMA by the Trump administration leave many residents feeling immense stress about the potential for assistance. With the impact of this storm on the cusp of an approaching winter, residents and first responders are left scrambling to provide desperate aid and restoration.

The Impact of the Trump Administration’s Cuts.

Rick Thoman, Alaska Climate Specialist, University of Alaska Fairbanks, took to The Conversation to publish his insights into the Y-K Delta’s storm recovery efforts on 14th October, 2025.

Did the loss of weather balloon data canceled in 2025 affect the forecast?

That’s a question for future research, but here’s what we know for sure: There have not been any upper air weather balloon observations at Saint Paul Island in the Bering Sea since late August or at Kotzebue since February. Bethel and Cold Bay are limited to one per day instead of two. At Nome, there were no weather balloons for two full days as the storm was moving toward the Bering Sea.

Did any of this cause the forecast to be off? We don’t know because we don’t have the data, but it seems likely that that had some effect on the model performance.

The Tough Choices of Recovery

With the Alaskan winter fast approaching, residents are left with the difficulty of deciding whether to leave the community for the winter, with the hope of rebuilding next summer. Housing and hotel infrastructure are scarce in the Y-K Delta. Typhoon Halong’s remnants smashed into an area that was already reeling from a housing shortage crisis.

Logistical complications affect the rebuild in the most remote places, like Kipnuk, where supplies must be floated in by barge. Aircraft can only fly with small amounts of supplies at a time. While the National Guard may be able to help with supplies, there are no longer runways to accommodate large cargo aircraft. Manpower is also needed to actually perform the work.

Rebuilding will almost certainly need to wait for next summer, and with constant cuts to Federal and State emergency response funds, it is unclear what these efforts would look like.

In terms of evacuation, it is also unclear what facilities may provide long-term hospitality. Currently, residents are sheltering in community buildings, like schools, while rescue and aid efforts continue. Some residents are forced to consider expensive housing options elsewhere, like Anchorage. To date, no long-term housing solution has been offered by the governments of the US or Alaska.

While recovery funding has come from The Alaska Community Foundation’s Western Alaska Disaster 2025 Relief Fund, and World Central Kitchen are both providing food to impacted families and first responders, the displaced need long-term shelter for the winter.

Residents are preparing to face this devastating hardship on their own.